I’m not going to give you a boilerplate intro to ChatGPT and Large-Language Models. I am not even going to bother asking ChatGPT to write me a boilerplate intro paragraph about AI that I can paste here.

Still. AI is here, and everywhere, and today’s post is the first instalment regarding connections between AI and Canada Declassified.

Some of you might have expected this: Mark Humphries and Eric Story had previously pointed to Canada Declassified in their excellent blog post “Today’s AI, Tomorrow’s History: Doing History in the Age of ChatGPT.” Mark also has a Substack about history and generative AI which I think is a must-read (especially the pieces describing his efforts to have students write essays with aI).

I have long hoped that the records on Canada Declassified could be used to create datasets and to automate… things.

“Things” of course is the operative word here. Just what do I want to automate and what do I not want to automate?

Is it time to worry? Yes.

First of all, I think historians should be terrified.

I mean terrified about what AI may do to our field. (I’m not even touching on teaching history today — that’s another story.)

Most people talking about AI think about ChatGPT and the chat interface — typing in text and getting text back. Too many people still assume that the only way to have ChatGPT conduct research is to paste text into the chat interface.

But ChatGPT itself has ALREADY moved WAY past that stage.

With the paid version of ChatGPT and a plug-in, you can ask ChatGPT to read any PDF you own or, more important for my purposes, any PDF for which you have a URL link. This means that ChatGPT can read, summarize, and create notes from any PDF that is available online, including on Canada Declassified. (I was using ChatGPT-4 and the ChatWithPDF plugin when I proved this to myself.)

It takes a bit of elbow grease, but it is possible to point ChatGPT not only to a single document, but to a collection of online documents, and ask it to read and summarize them.

(I should add here that, of course, if the text of the primary documents is already available online, not as a PDF but like the text on this page, then this is even easier to do. I’ve just started fiddling around with asking ChatGPT-4 and the plugin “BrowserOp” to read groups of documents from the Foreign Relations of the United States series and then provide me with a historical narrative based on these records.)

My view is that the paid version of ChatGPT can already produce something that looks very much like “history.” It is not real historical work. It lacks context, judgment, etc., and would be recognizable to historians and subject experts as “off.”

But most people aren’t historians, and most people don’t want to be. They might just want to read history from time to time.

Already, magazines that accept short fiction stories have had to stop accepting submissions because they cannot determine which submitted stories have been written by a human and which have been written by AI.

If you had any hope that this is a problem only for fiction writers, and would not impinge on the world of non-fiction, I have bad news.

We are going to be absolutely flooded with garbage “history” (along with garbage-everything-else, too.)

Does me worrying about AI mean I’m not going to try and automate boring stuff? No.

My example for today is much more boring and less scary. It has to do with automatizing… footnotes!

Footnotes, baby steps, foot… steps… see?

For the last fifteen years historians have been using applications like Zotero to automatically format secondary sources. Our university libraries are set up to sort this out for us. If you find a book in the library catalogue, or download a journal article, you also get the citation info in your software and, in turn, you can plug it straight into your essay, article, book etc., in whatever citation format you select. Boom. Easy.

It has long been my hope to have the ability to automatically format and insert citations for primary documents. And I want to be able to do it at scale.

This is where Canada Declassified comes in.

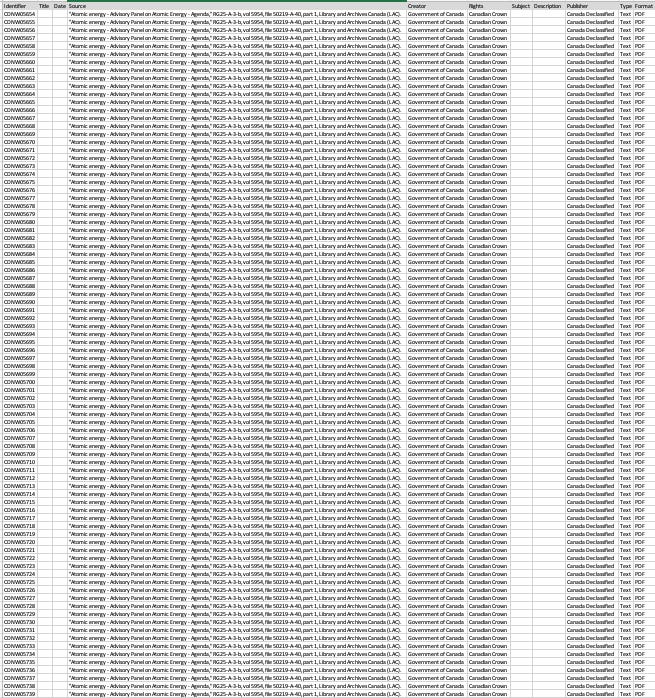

When we upload PDF documents to Canada Declassified, we have to create a spreadsheet that includes information about each document.

This is what allows you, as a user, to see information about the document including, especially, its archival source.

And we now have a lot of documents up on Canada Declassified. Over 30,000, almost all of which will be publicly available soon.

When I am doing my own research, my rough work, and most of my drafting I use the Canada Declassified identifiers - the letter and number code like CDVN00001 above - as a placeholder rather than write out a full footnote. This is useful because if I want to look at the primary source again, I just search for that CD number and I have the original document right in front of me.

As a very last step, I then go back and add in the archival information note-by-note. This has been okay for three articles I’ve written this way - articles aren’t that long. It was more of a challenge for the book manuscript I just finished.

This is one of the things that I do want to automate: I want to be able to click a button (or two) and have my computer transform all of the identifier numbers in my draft into full archival references.

I have long understood this was possible but I simply did not have the skills to do it. Microsoft Office programs are supported by a Visual Basic Editor which is basically a little programming thingie where you can write a code and ask it to take information in your Word document and replace it with other information. (And it can do other stuff, too, all beyond me.) The set of instructions, or program, that Office programs can runs called a “macro.”

This is where ChatGPT is so useful. I just told it what I wanted to achieve. And, it turns out, I don’t have to be a programmer to program.

I explained before to you what I wanted to do. I did the same thing with Chat GPT. I told ChatGPT what I wanted and asked ChatGPT it to write me a macro. (Because, again, I have NO IDEA how to write a macro.)

It gave me some code.

And then I made a whole bunch of mistakes.

I tried to run the macro in Word, not Excel. No dice.

Then it did not work for footnotes, but only for text in the body of the document. Easily fixed.

I fiddled around a bit with the commas and spacing I wanted in citation.

I used a small spreadsheet (3 rows) and it worked fine. Then I tried a spreadsheet with 10,170 items and it did not work. ChatGPT helped me modify the code to manage a longer list.

Then I thought it kept crashing. I realized maybe it just takes a little while. So I did some laundry. I came back and voilà, it had worked by the time I came back.

And to be clear, when I wrote above that ChatGPT “helped me modify the code” I am just being fancy. What really happened was:

a) I told ChatGPT that something didn’t work and copied the error message (which meant nothing to me).

b) it told me there were a few ways to fix the problem, and listed different methods.

c) I picked one of those methods and asked ChatGPT to re-write the code by the method I had selected.

d) It produced new code.

e) I deleted the old code and pasted the new code.

If I look really carefully I can sort of understand how the code changed (actually, ChatGPT puts in some pretty handy explanatory notes in the code.). But guess what. It doesn’t matter. I don’t care.

Because it worked.

When I ran the perfected macro, I got (almost) exactly what I wanted: A full note along with the Canada Declassified identifier. (With find and replace, it easy to turn these into short notes, getting rid of the full “Library and Archives Canada,” for instance.)

I say “almost” because, at the moment, I have no idea why the note is all capitalized. I’ve tried to fix that but no luck yet. I’m confident I can figure it out. Or should I say that I am confident ChatGPT will help me figure it out?

Next steps

Currently, I have some Canada Declassified spreadsheets with detailed file information like in the example above. By detailed, I mean spreadsheets that include each document’s title and date.

But most of the 30,000+ items currently exist in spreadsheets with archival reference information but not title and date.

A long time ago I made a trade-off: Get more documents up on Canada Declassified instead of spending time completing these two metadata fields.

It seemed to me far better to get the documents up there with only archival references, and people (including me) could just determine the name and date for each document to be cited in a publication. At that time, I had no macro. And it worked well enough.

The next challenge will be: How can we use AI to help easily and accurately identify a document title and date from each primary document?

It is my loose understanding that this is not impossible and has in fact been possible for some time.

If I can create such a detailed spreadsheet, filled with the titles and names of all the documents, I can post it on Canada Declassified and others can download it. Everyone working with these documents could use this method to cite these records, allowing more time for reading and analysis and writing, and less time spent formatting citations.

Sounds good.

Except that I don’t know how to do it.

And ChatGPT is not going to do it for me.

But I am hoping that it might help me find out how to do it.

More sources if you are thinking about AI and History or higher education:

Mark Humphries’s Substack is called “Generative History.”

Ethan Mallick is a Wharton Prof who is doing the most interesting work on AI in the classroom and in higher education. His Substack is “One Useful Thing,”and I also recommend this podcast episode from the NYT, beginning around the 22-minute mark. (A tip of the hat to an associate dean at UofT for mentioning the podcast to me!)